How Juvenile Justice Reform Has Impacted Child Welfare & What We Must Do To Fix It

On October 16, 2019, Dr. Linda Bass of KVC Kansas testified about the impact of crossover youth in foster care at the Joint Committee on Corrections and Juvenile Justice Oversight in Topeka. Here is the full testimony she shared.

KVC Kansas is a nonprofit organization that provides child welfare and behavioral health services to over 30,000 Kansas children and adults each year. We are passionate about high-quality prevention services that strengthen families and reduce their involvement with the child welfare and juvenile justice systems. This is what is in the best interest of children and families.

We know that, in large part, Senate Bill 367 was created to prevent youth from growing up in detention centers. We support this effort 100%. No child should grow up in an institutional setting. In fact, our own track record over the last 20 years shows that we helped dramatically reduce the use of congregate care for children in foster care. In 1996, when we started providing foster care case management, 30% of children in foster care were cared for in congregate care settings like group homes. Knowing that children grow best in families, we helped the state reduce that number to just 4% of children in foster care. We provide training and consultation around the world on how to right-size congregate care while serving children in family-like settings. In fact, most youth can be served safely in their own homes with the right services and support.

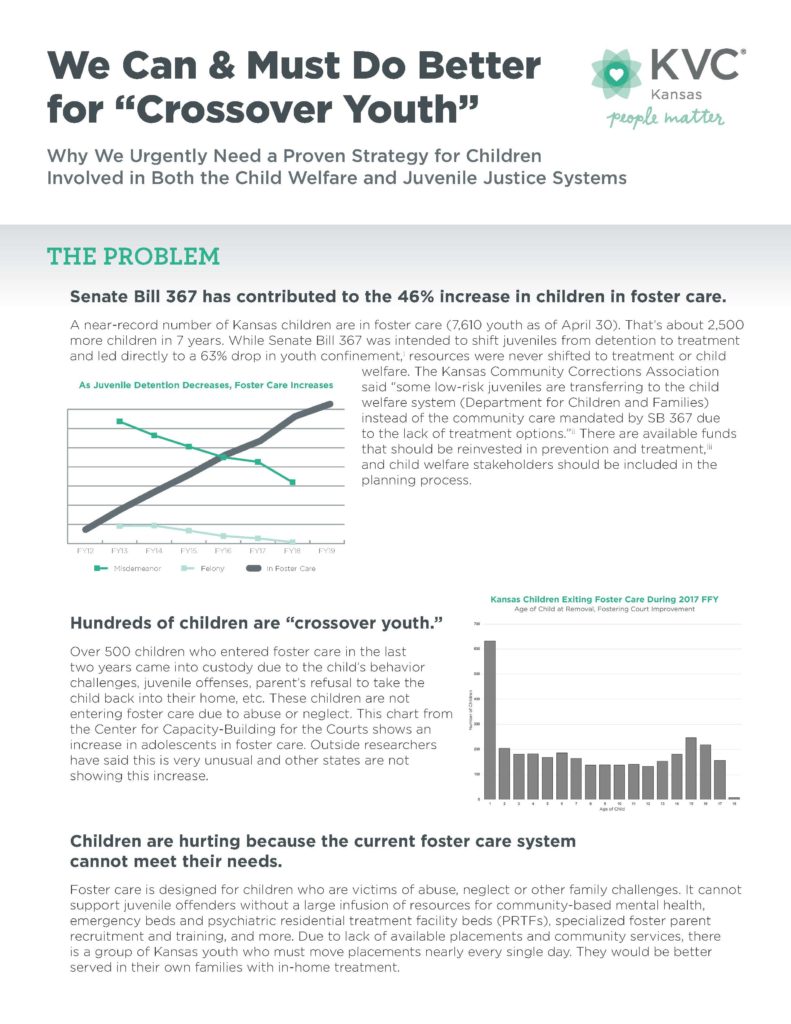

Unfortunately, SB 367 did not provide the necessary services and support to appropriately support youth to remain safe at home. While it did lead to a 63% drop in youth confinement and is often considered a success from that narrow perspective, it fails to consider what happened in the Kansas child welfare system. Since 2011, the number of Kansas children in foster care grew by 46% or by approximately 2,500 children. Approximately 1,000 of those children were added since SB 367 went into effect.

No new resources and no additional training were added to the child welfare system to help serve these children and their families, particularly those who may have behavior challenges that would have previously been served by the juvenile justice system. As a result, youth who are placed in foster care due to behaviors that would have previously led to involvement with the juvenile justice system have been failed by both systems. The youth who are referred to child welfare as crossover youth are experiencing high rates of placement instability, lack of access to treatment and education and are less likely to reunify timely. As a state, we can and must do better.

SB 367 coupled with other statewide changes has led to insufficient service array for children and families

To be clear, SB 367 is not the only or even the largest contributing factor to the exponential rise in Kansas children in foster care. In February 2018, we shared an infographic that listed six contributing factors to the foster care growth.

Those six factors are:

- Low spending on prevention compared to other states

- Reduced spending on safety net services and community supports

- Reduced spending on mental health services

- Lack of substance use treatment options

- More juvenile offenders in care

- The need for an evidence-based safety and risk assessment to ensure children only enter foster care when there is no other safe option.

It is the combination of these factors which has created a dangerous situation for children, families and professionals. There are thousands more kids in the foster care system at a time when there have been devastating mental health funding cuts, a 65% reduction in the number of PRTF beds in the state, and no extra training or resources to help this population of youth and their families.

How do we know that SB 367 led to children who would have previously been served by the juvenile justice system now being served in the child welfare system?

1. More Children Entering Foster Care for Non-Abuse/Neglect Reasons

Kansas has a high number of referrals that are non-abuse/neglect cases (Child in Need of Care – Non-Abuse/Neglect, or CINC-NAN). This is now referred to as Family in Need of Assessment (FINA). According to DCF data, 26% of the children who entered foster care last year (1,072 children) did so for non-abuse/neglect reasons. While not youth referred to child welfare as FINA are crossover youth, we estimate that KVC served approximately 200 crossover youth in our half of the state last year, which might equate to 400-500 youth statewide.

To be clear, child welfare has always served youth with complicating behaviors such as running away from home, truancy, theft, and drug use. The child welfare system is properly equipped to support and treat youth with these types of behaviors and needs. The severity of crossover youth behavior since SB 367 far exceeds what the child welfare system was prepared and resourced to properly handle. At the point of referral to foster care, parents report fearing for their own safety or the safety of others in their home. Caregivers report that they have not been able to access needed supports and services in their community and therefore, they view foster care as their only option.

Families are often misinformed that the foster care system is set up to care for these youth. The outcomes for these children are poor at best and more often foster care causes more harm to crossover youth as well as those placed with these youth. Crossover youth in foster care have a more difficult time maintaining placement stability which then leads to frequent school and mental health service changes. These youth often incur additional charges while in care while also placing other youth in foster care at risk for future victimization.

Kansas is also different from other states in that it has more teenagers entering foster care. The Capacity Building Center for Courts has data showing that this does not match what is happening in most other states (National Data Archive on Child Abuse & Neglect, (NDACAN).

2. Need to Create New Youth Care and Security Officer Positions

Since SB 367 went into effect, KVC Kansas has had to create and hire positions and placement options that we have never needed in child welfare before. We have hired, trained and paid for these positions at our own expense. We created a position called Youth Care Specialist, which are staff who are responsible for caring for children waiting for placement during the day and night, which are nearly always crossover youth. We have had to hire full-time security officers to respond to the trauma that’s occurring in the office when crossover youth become violent with staff or other children. We have had numerous security officers and law enforcement officers who have declined providing security services in our buildings due to the violent nature of the crossover youth in our care. We have added more than 20 FTE positions to respond to the unique needs of crossover youth and improve safety of the children, caregivers and staff who are working with these youth.

We have worked to identify and provide a series of specialized trainings to better respond to needs of these youth. Many of our youth care specialists and case managers report feeling completely unprepared to respond to the needs of crossover youth. Most staff and caregivers report feeling fearful to work with these youth.

3. More Kansas Foster Families Closing Their Homes

Most people become foster parents to care for children who have experienced abuse or neglect. While childhood trauma can certainly lead to behavioral challenges, foster parents are not equipped to handle the severity of behavior challenges that crossover youth often exhibit. Foster families report being fearful for their own safety as well as for the safety of their biological children and other foster youth in their home.

Numerous foster parents have closed their homes after caring for crossover youth who are not appropriate for foster level placements, however, no other options existed. With 7,500 Kansas children in foster care and appx. 2,700 foster families, we as a state cannot afford to lose any foster families.

4. Significant Costs to Safely Care for Youth with Behavioral Challenges

While SB 367 was intended to keep kids out of institutional care, unfortunately in order to maintain the safety of the crossover youth and those around them, many of them have ended up in a newly created level of care; non-Medicaid reimbursed acute psychiatric care. While at first glance an acute care setting may appear to be an improvement over detention, this is also not an appropriate level of care for these youth. Without other appropriate placement options, this has been the most secure option available for crossover youth who are unsafe in family and group home settings.

This level of care did not exist prior to SB 367. The cost of care in an acute psychiatric residential setting far exceeds the reimbursement for their foster care. Over the last few years, KVC has use 774 such placements (we call them Letter of Agreement or LOA) for 414 distinct children. Total length of stay in an acute setting for all 414 crossover youth amounts to 23,245 days. Since SB 367 went into effect, KVC has had to contract with various placement providers for LOA acute level placements in order to keep children safe who are unable to be placed in a lower level of care. The cost of these placements has exceeded $13 million dollars.

5. Other Children and Staff Have Been Victimized

In the last few years, crossover youth in foster care have repeatedly threatened and assaulted child welfare professionals, foster parents and other children in foster care. We have had countless incidents of assault on staff, caregivers and children, weapons in the office (youth pulling guns, knives, and scissors on staff and other children), significant property destruction (stolen and crashed vehicles, destruction of office equipment, theft of staff personal property), drug use, serious bodily threats, broken bones, bruises, cuts, etc.

Law enforcement’s response to dangerous behavior has been severely limited by SB 367. Often within hours of assaulting a KVC staff member, foster parent or child, KVC is required to pick up the perpetuating youth and bring them back to the office. Crossover youth report to KVC staff and caregivers that they are aware that there are no consequences to their actions.

6. Dangerous Situation Has Contributed to Child Welfare Staff Turnover

Because of the safety concerns, the problem of crossover youth in child welfare without additional resources has contributed to the already-high turnover of child welfare professionals. Staff report feeling scared to come to work and threatened by the youth on their caseloads.

Moving Forward – There Are Many Solutions

Youth at risk to enter the JJA and CINC systems need a more responsive, robust intervention that can support youth to remain safe and home in their community and group up in a family setting.

KVC Kansas has proposed the following solutions:

- Create a more flexible definition for how reinvestment dollars can be utilized.

- Use funds to prevent at risk crossover youth from entering the JJA and CINC systems. Current definitions are too restrictive and do not allow for services and supports to be delivered before a child enters the JJA or CINC system.

- Use funds to train and support current JJA and CINC professionals to intervene more effectively with crossover youth and their families.

- Require more comprehensive data tracking and sharing across systems (JJA, CINC, court, etc.). Data should be used to identify at risk youth so that assessment and services can be offered prior to youth becoming deeply involved in JJA or CINC systems

- Allow law enforcement greater flexibility in their response, so that they can connect youth and families to the right resources at the right time.

- Increase capacity for respite and treatment options for crossover youth.

- Repurpose detention beds into treatment/respite beds and secure care beds for crossover youth. Require a strong family engagement and treatment component.

- Increase availability of PRTF beds

- Invest in high-quality prevention services for youth at risk of becoming crossover

- Increase access to and require family preservation prior to out of home (CINC) placement for all non-abuse neglect (CINC)/families in need of assessment (FINA) cases.

- High quality prevention services cost approximately $5,000- $10,000 per family and have solid outcomes while foster care services for crossover youth cost on average $80,000 or more per family and the outcomes are poor. Crossover youth are more likely to age of care without connection to a support system. Youth who age out of care are more likely to end up homeless, incarcerated and face significant mental and physical health challenges. Prevention and early intervention are key.